Last Updated: February 10, 2021

By Andrew Duguay, Chief Economist

Data updated: May 6, 2020

An important topic that is looming in the background of recent headlines regarding stimulus debts and deficits warrants deeper evaluation. Deviating from some of the short-term topics may not seem relevant, but in context, it’s crucial in reference to the unprecedented levels of spending both from the federal government with trillions in stimulus money, as well as what we see from a monetary policy standpoint.

Many may be wondering if stimulus infusions will alleviate the pressure of recession sooner rather than later. Does this have implications for the next few years as we’re planning out? Or does this essentially delay to a future point where some of these deficits may more significantly impact the economy? Let’s examine debts and deficits a bit deeper to glean impact on the short- and long-term ramifications to the economy.

Health Crisis Opening Up and Leading Economic Signals

To begin, it’s essential to acknowledge that we remain in a health crisis here in the United States and around the world. We know that the side effects of this health crisis are the shelter in place restrictions, which have naturally led to an economic crisis.

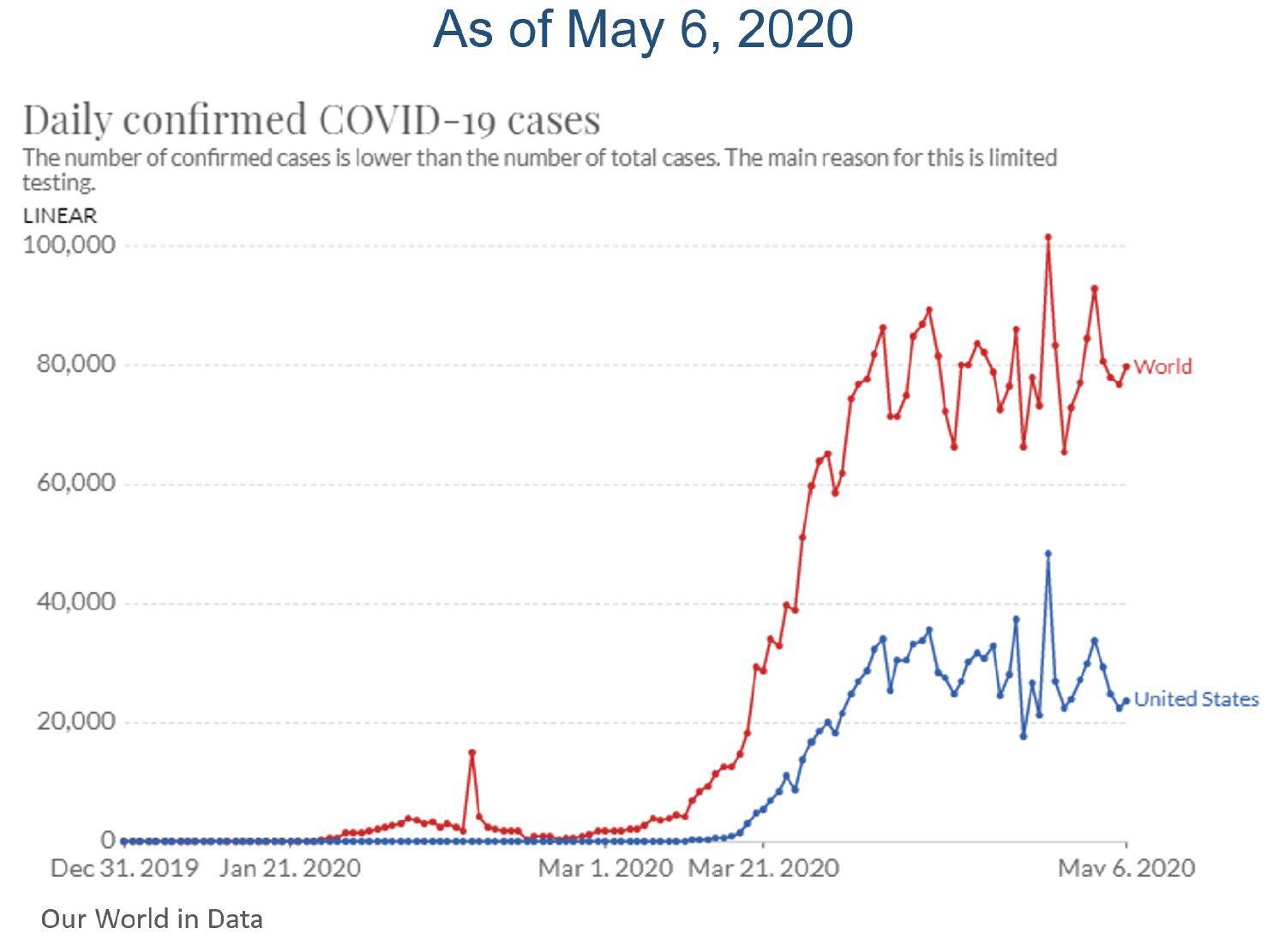

As purveyors of data, Prevedere analyzes the multitudes of economic data emanating from this pandemic situation. Our role is to evaluate the economic ramifications of a crisis that is still largely tied to COVID-19. To begin, we take an updated look at the number of daily confirmed new COVID-19 cases to determine if we are “bending the curve” by reducing the rate of increase in cases as well as the number of new cases. As you can see, we have possibly reached this level.

In a review of world figures or even US figures, we don’t have to look back very far to see the number of new virus cases today remains elevated, particularly compared to where we were a couple of months ago. The moment in history is significant as we shift our collective attention to the reopening of the US economy. Businesses forced to shut down because of COVID-19 are starting the process of becoming operational again. This movement serves and a beacon of financial recovery.

In consideration that “bending the curve” is the admission that we continue to remain on a curve, as the health problem remains active. The number of new cases is still at an elevated level, and it’s going to take a while to curtail to a place where we all feel confident in our normal economic actions again. Indications suggest the economic impact will be significant, so long as we are still hoovering on the curve, and therefore we should expect additional months and quarters of suppressed economic performance.

As we look at the health-related data for some context, we realize that reopening business is only the beginning. It’s a step in the right direction, as workers who were previously temporarily unemployed can start working again and contributing to the economy. However, continued social distancing will continue to be strongly encouraged because the number of new cases is still at elevated levels. This all leads to the conclusion that consumers are going to continue to change the way they behave. We must consider this when looking at overall economic recovery scenarios.

Consumer Sentiment

In preliminary data coming from China, spending across categories remains well below pre-COVID levels. Why is this significant? We need to consider that China’s economy was previously growing at a rapid pace and that they had contained the virus in relatively short order compared to the United States and many other countries, with few new cases reported. What we’re seeing are strong hints that the post-pandemic world, even after the number of reduced virus cases to virtually zero, it is still a very conservative economic environment.

In effect, consumers are not going to spend the same way that they spent before COVID-19. For the United States, we still have a road ahead of us. When we talk about diagnosing our economic projections, this data solidifies the extrapolations from our economist team that we are not looking at a V-shaped recovery. There are still hopes of a U-shaped recovery depending on conditions tied to the projected outcome of COVID-19 and how we continue to contain it. But even so, this will not be a quick recovery.

On a positive note, there is a considerable opportunity given the economic landscape. We’re observing people helping each other out by supporting small businesses. We also see unprecedented levels of support from our government in terms of increased unemployment payouts and stimulus packages designed to help large and small businesses alike.

Additionally, the Federal Reserve is following up with an aggressive monetary policy to back up not only what Washington DC is funding, but also support for the financial markets to ensure enough liquidity for businesses who need to borrow. In summary, it’s going to take a while for the recovery to progress. In the meantime, the US government has taken extraordinary steps to help with an unprecedented stimulus to benefit the people.

Deficits Are Not Overtly Damaging

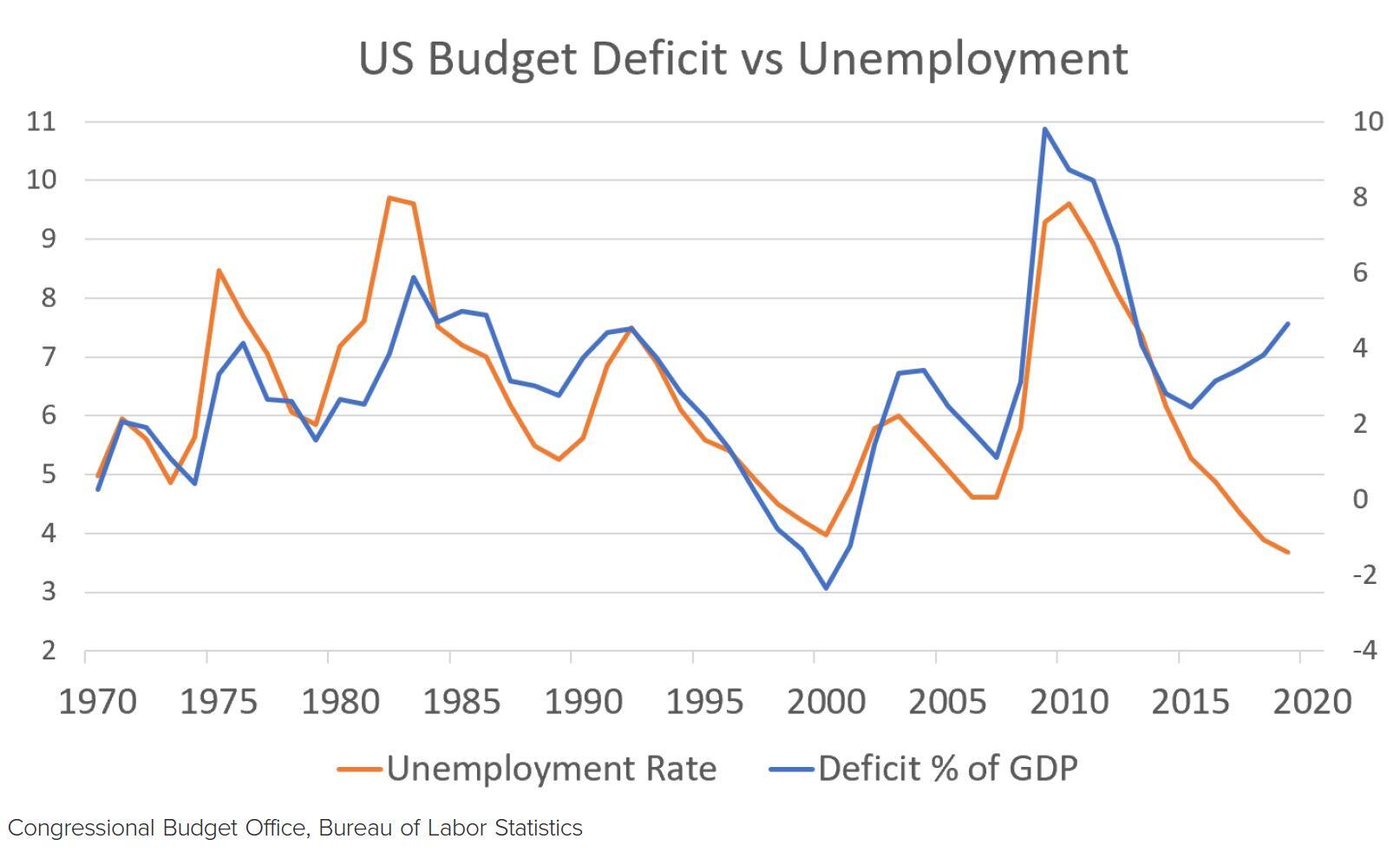

This chart shown above is significant because it shows a long-term historical view of the US budget deficit as a percent of GDP compared to the unemployment rate. What we see historically is that there is a strong relationship between falling unemployment and economic growth. Further, the deficit as a percentage of GDP also tends to fall. Subsequently, when the economy starts to slow, you tend to see budget deficits rise.

These cycles have happened repeatedly over many different recessions over many different decades. Consistently, deficits tend to fall when unemployment rates fall. Interestingly, for the first time in modern history, we saw a strong deviation from this trend, beginning in 2016. In 2016, unemployment rates continued to fall, the economy continued to grow, but our deficits did not decline. And we started to see our deficit as a percentage of GDP start to increase year-after-year, to where we are today. This isn’t all that important on its own, but it does set the context for a remarkable fact, that every business cycle is setting itself up for the next future business cycle, by deficits falling during good times so they can rise during bad times. Over the last few years, we have deviated from this trend, not allowing deficits to fall during the “good times” of low unemployment preceding this crisis.

Largely stated, governments can’t take the business cycle away in the long run, but they can either dampen or deepen it in the downturn. In our current COVID-19 economic crisis, we’re experiencing a great example of government dampening the downturn because of the unprecedented levels of stimulus. However, the ability to dampen future downturns and bolster the upturns depend on policy during the good times of economic growth as well. And this is where we look through the recent history of the last four or five years to see that maybe we weren’t as fiscally prudent- as we should have been ahead of this downturn.

The Keynesian policy playbook that we have been playing for many years says that we spend during downturns to support the economy. Most of us would largely agree that that is a good thing. We are supporting the economy in this vulnerable time rather than becoming more conservative. However, our ability to continue to do that depends on that blue line declining during the good economic times. Where will this leave us in 2021 or 2022 after this recession is over, and we resume with normal trends and expect unemployment rates to go down? This affects the projections for the deficit and unemployment beyond 2020.

The orange line is the unemployment rate, as suggested by a poll from the National Association of Business Economists. The median projection for unemployment at the end of 2020 is around 9.5%. This puts us pretty much in line with the last recession, maybe slightly lower. There’s considerable temporary unemployment in this event, but we think by the end of the year that the unemployment rate will hover around 10%. However, our deficit is not going to be where it was in the last recession. It’s projected to balloon to approximately 18% of GDP. This means that we’re left with similar unemployment rates to the last recession. However, we will realize debt and deficits more in line with numbers that we hadn’t seen since World War II when we had massive increases in debts and deficits to fund the war effort.

It’s an interesting exercise to find learnings from so far back. The World War II debt had to be paid off in the subsequent decades afterward. This is similar to what we anticipate and what we mean when we refer to setting ourselves up for the next downturn. If our starting point this time is around 18%, how much more do we have to reduce that to get back in line with historical trends to be well prepared to assist during the next economic downturn?

The positive news when thinking about the next six, 12 months, or even 24 months, is that the rooster doesn’t have to come calling very soon. Deficits are not overtly damaging in the near term. This has proved beneficial for many developed countries such as the United States, Europe, and Japan. Where we know nations have run large deficits for long periods and have very minimal overt consequences. If debts and deficit obligations are backed up by a strong currency and by a government that pays its bills in an economy that can show some economic growth, then what you have is deficits that can grow for many years without turning into inflation.

The Inflation Myth

It’s a large misnomer that deficits automatically turn into inflation. We are not arguing for the Federal Reserve to print money to stimulate the economy. However, news outlets and talking heads put out more than enough speculation about deficit spending spurring ridiculous amounts of inflation, and we’ve learned from modern economic history that that’s not necessarily true. Look no further than Japan to see an example of a country that can rack up huge deficits and not necessarily have high levels of inflation.

When viewing inflation, the interesting tie-in is that deficits are relatively benign until you face inflation. Inflation can come from many different angles, but when inflation does arrive, that’s when deficits become a real problem because you must rollover your debt, and higher elevated rates of interest payments become notably expensive. This kind of inflation forces governments to make a few different decisions. All of these look ugly. None are good outcomes for an economy.

Inflation combined with high deficits is usually remedied in one of three ways.

1. Either you can start raising taxes, which will reduce that deficit.

2. You can cut spending, which will also reduce the deficit explicitly.

3. You could suppress interest rates to be below inflation rates, which is a backdoor way of taxing those that save because their savings are getting inflated out.

The government is benefiting by having lower rates of borrowing costs from their interest rates than what inflation rates are. If you look back to when we last had debts and deficits like the current era, post-World War II, we had several different approaches both in the United States and around the world using a combination of very high taxes, very conservative spending levels, and monetary and fiscal policies that suppressed interest rates below inflation rates.

In comparison, over the last 20-years, we haven’t experienced any one of these three approaches. We’ve increased our spending, and we have lowered taxes. We’ve seen an environment where interest rates are low, but inflation rates are even lower in the United States. And that has been a boon to the economy.

What remains to be determined is, can these three approaches be sustained to see a new cycle of economic growth? What we may notice is that the United States might not be held accountable for actions until the next downturn when we are in a financial struggle starting from a high level that we can’t stimulate our way out of the next recession as we have with this downturn.

The New Normal

The next downturn may be more or less severe, but the increasing concern should be in our ability to fight the next downturn with a monetary and fiscal policy because of the fault of not reducing our debt-to-GDP ratios in past economic cycles. The takeaway from this dialogue is that it serves little purpose to bring up debts and deficits during downturns compared to any other periods. People like to talk about deficits during a recession because that’s when deficits tend to get worse. And while this all makes for fantastic headline news, but its a directionally normal trend. What should have been concerning is deficits as a percent of GDP is rising, while unemployment has been falling in the previous five years.

Conclusion

A typical approach during a downturn is to stimulate the economy. We also need to consider that it’s just as crucial during the downturn as during the upturn to employ a level of fiscal prudence so that we approach every downturn with the ability to stimulate the economy because we kept our debt in check during the preceding economic growth period. In the coming economic upturn, our country will have to ask ourselves, how do we slowly chip away at some of these gaps that we’ve seen between the debt-to-GDP ratio and economic growth to set ourselves up for the next economic downturn? We may face tough choices during the economic recovery about reducing deficits that may slow economic growth, or if we leave those tough choices ignored, we may face a future recession without the fiscal and monetary aggressiveness we are applying to this downturn.

***

Economic Scenario Planning in a COVID-19 World

Planning and forecasting based on historical performance is no longer valid in today’s economic climate. As you look ahead beyond the immediate crisis and consider your business plans, having visibility to external economic factors and being able to consider how your company will fare in the “new normal” economy are paramount. This is what we call Intelligent Forecasting.

Prevedere helps companies answer, “what’s next?”, using global data and AI technology.

Whether it is a black swan event like the COVID-19 pandemic, less severe shocks like falling oil prices, or the regular contraction-expansion business cycles, Prevedere provides executives with insights on global forces impacting their business.